Language models can answer medical questions with surprising accuracy. But do they actually encode medical knowledge in identifiable, interpretable ways? Or is it all just statistical soup?

Using Neuronpedia, we ran a simple experiment to find out. We searched for features related to angina (cardiac chest pain) inside Gemma 3 1B IT, then tested whether those features light up when the model processes related medical prompts. The short answer: they do, and the results are pretty clean.

What Are Features, and Why Should You Care?

Sparse autoencoders (SAEs) decompose a model’s internal activations into interpretable directions, often called “features.” Each feature corresponds to a concept the model has learned. Neuronpedia hosts pretrained SAEs for several open models, including Google’s Gemma family, and lets you search, inspect, and test these features through a browser interface.

If we can find features that reliably correspond to specific medical concepts, that tells us something about how the model organizes its knowledge. It also opens the door to monitoring, steering, or auditing model behavior at a mechanistic level.

The Experiment

Step 1: Search for “Angina”

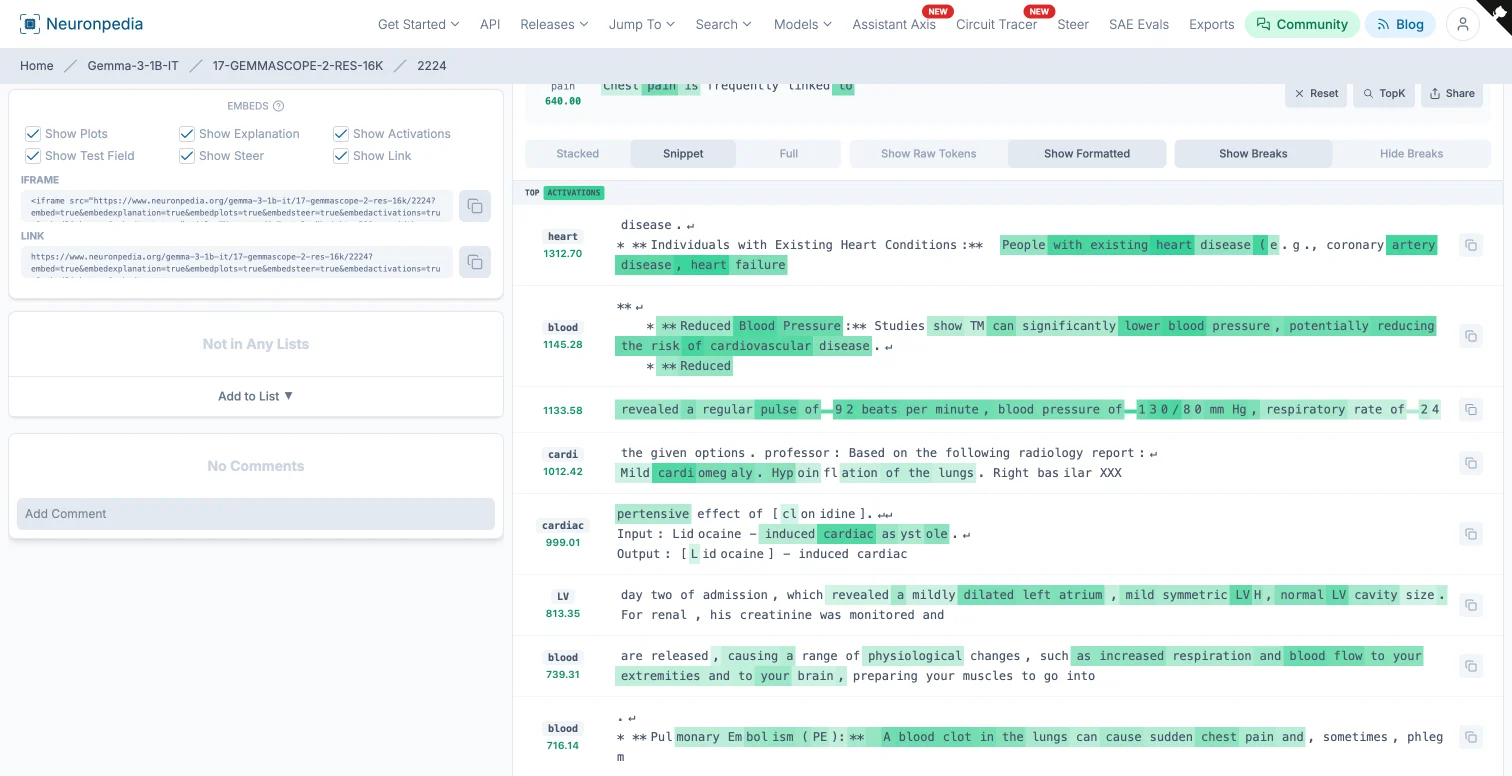

We used Neuronpedia’s “Search via Inference” tool with GEMMASCOPE-2-RES-16K (Residual Stream, 16K features) across all layers. The search surfaced several candidate features. One stood out: “cardiac and blood flow” (feature 2224 at layer 17).

Its top activations included phrases like “Individuals with Existing Heart Conditions,” “coronary artery disease, heart failure,” and “Reduced Blood Pressure.” The positive logits pointed to tokens like “Heart,” “cardiac,” and “cardiovascular.” So far, this looks like a genuine cardiac concept feature.

Step 2: Test It on a Medical Prompt

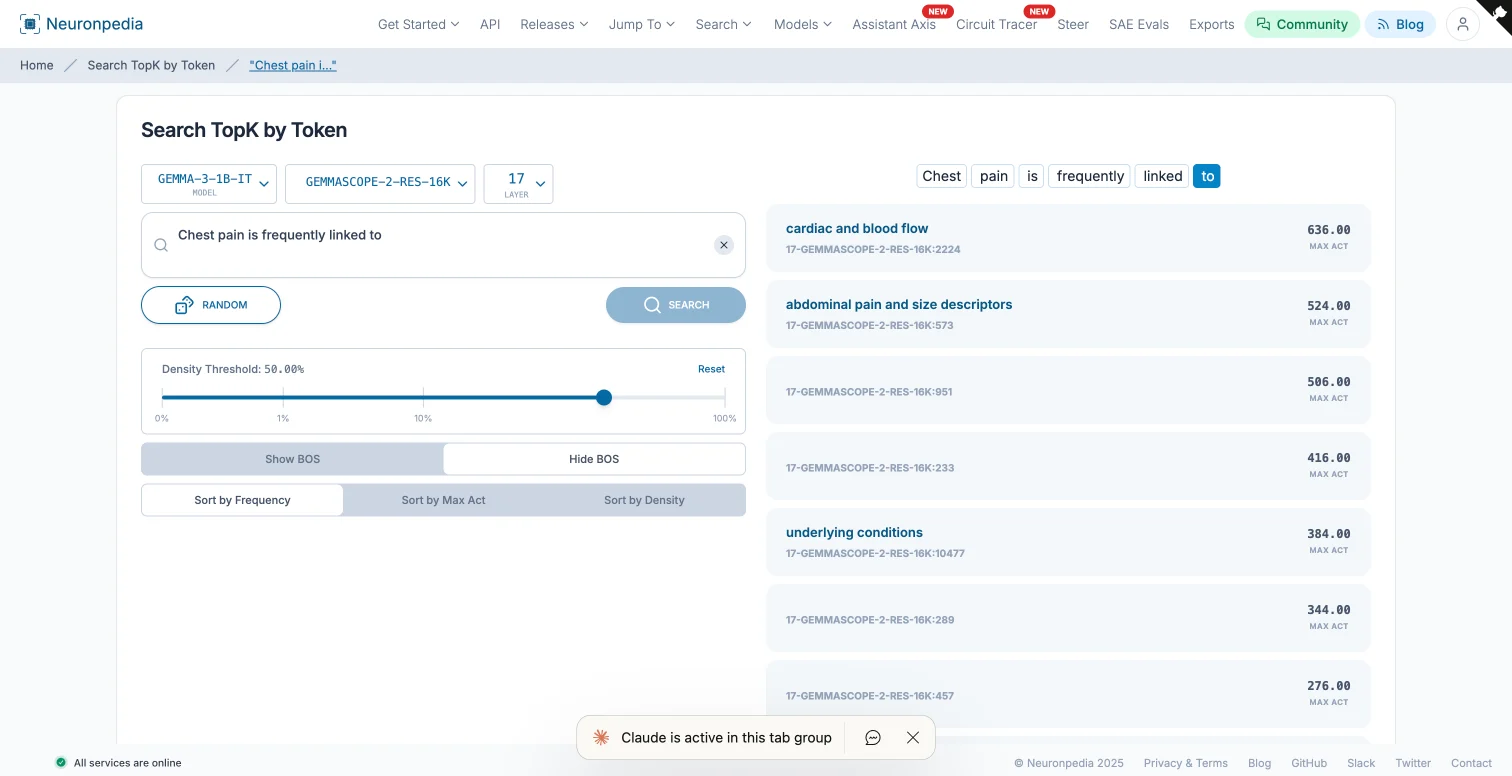

Here’s where it gets interesting. We used Neuronpedia’s TopK feature analysis to see which features activate most strongly at the final token when the model processes:

“Chest pain is frequently linked to”

This is the exact position where the model predicts the next token. If the cardiac feature actually encodes what we think it does, it should activate here.

Result: The “cardiac and blood flow” feature ranked #1 at the final token position, with an activation of 636.00. Not buried in the top 50. Not somewhere in the middle. Number one.

Step 3: Replicate with a Different Medical Domain

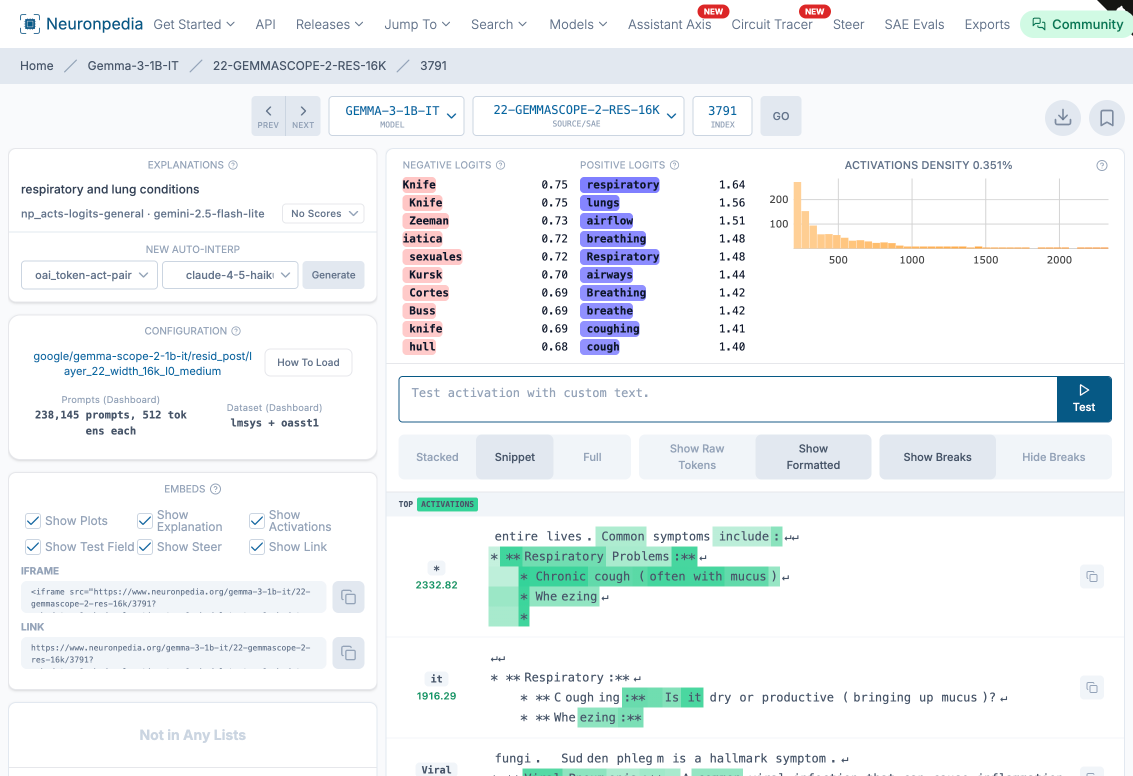

We repeated the experiment for respiratory features.

Searching for “pneumonia” surfaced a feature called “respiratory and lung conditions” (feature 3791 at layer 22). Its positive logits included “respiratory,” “lungs,” “airflow,” “breathing,” “airways,” and “coughing.” The top activations contained clinical text about chronic cough, wheezing, and respiratory problems.

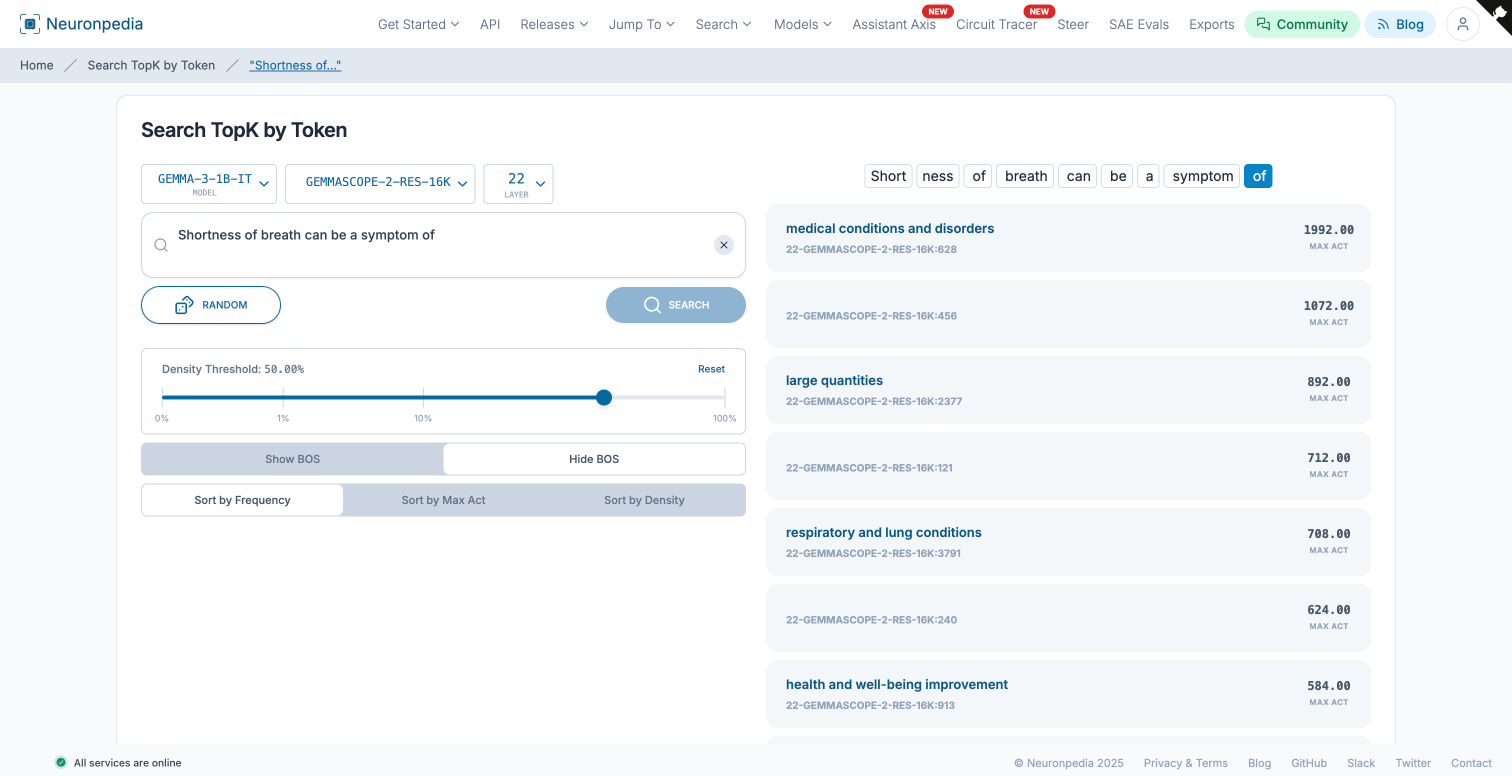

We then tested this feature against the prompt:

“Shortness of breath can be a symptom of”

The TopK analysis at the final “of” token showed the respiratory feature at 708.00, landing in the top 5. The top feature was “Medical conditions and disorders” at 1992.00, which also makes sense since shortness of breath can be a symptom of many things beyond just lung conditions.

What This Tells Us

Both experiments follow the same pattern: features discovered through symptom-related searches activate strongly when the model processes related medical prompts. The cardiac feature found via “angina” fires at position one when the model encounters “chest pain.” The respiratory feature found via “pneumonia” fires in the top five when the model encounters “shortness of breath.”

This isn’t proof that the model “understands” medicine in any deep sense. But it does show that Gemma 3 1B IT organizes medical knowledge into identifiable, interpretable features that activate in contextually appropriate ways. The model isn’t just pattern-matching surface tokens. It has learned something about the semantic relationships between symptoms and conditions.

Limitations

A few caveats are worth noting.

This experiment only tests two medical domains (cardiac and respiratory). A broader study would need to cover many more domains to make strong claims about generalizability. We also only tested one prompt per domain. More diverse prompts, including edge cases and adversarial examples, would strengthen the findings.

The activation values themselves are hard to interpret in absolute terms. Is 636.00 “high”? Relative to what? The ranking (first place) is more meaningful than the raw number.

Finally, this was done on Gemma 3 1B IT, a relatively small model. Larger models may organize their features differently.

Try It Yourself

The whole experiment is reproducible through Neuronpedia’s web interface. No code required.

If you’re interested in mechanistic interpretability for medical AI, this is a good starting point. Search for a medical concept, find its features, then test whether they activate on related prompts. It takes about five minutes, and the results can be surprisingly informative.