Off late a lot of my research time is studying why medical models systems fail. Not the obvious failures where the model outputs gibberish, but the subtle ones where the output looks clinically appropriate, follows proper documentation structure, uses correct terminology, and is still wrong.

To illustrate this problem, I trained a small GPT-2 model from scratch on clinical notes. The goal was not to build something useful. The goal was to demonstrate how easily language models learn to mimic clinical language without learning anything about clinical reasoning.

The results should concern anyone deploying LLMs in healthcare settings.

The Setup

I built a 7.7 million parameter transformer and trained it on two publicly available datasets: MEDIQA-Chat (67 doctor-patient dialogues with paired clinical notes) and MTSamples (approximately 5,000 medical transcriptions across 40 specialties). Total training data was around 200,000 tokens.

For context, GPT-2 was trained on 10 billion tokens. My model saw 0.002% of that amount. It trained for about 15 minutes on a single GPU.

Open this experiment in Google Colab and run it for free

How the Model Works: A Brief Primer

Before showing you what the model produced, it helps to understand what it actually does. This is a simplified explanation for readers without a machine learning background.

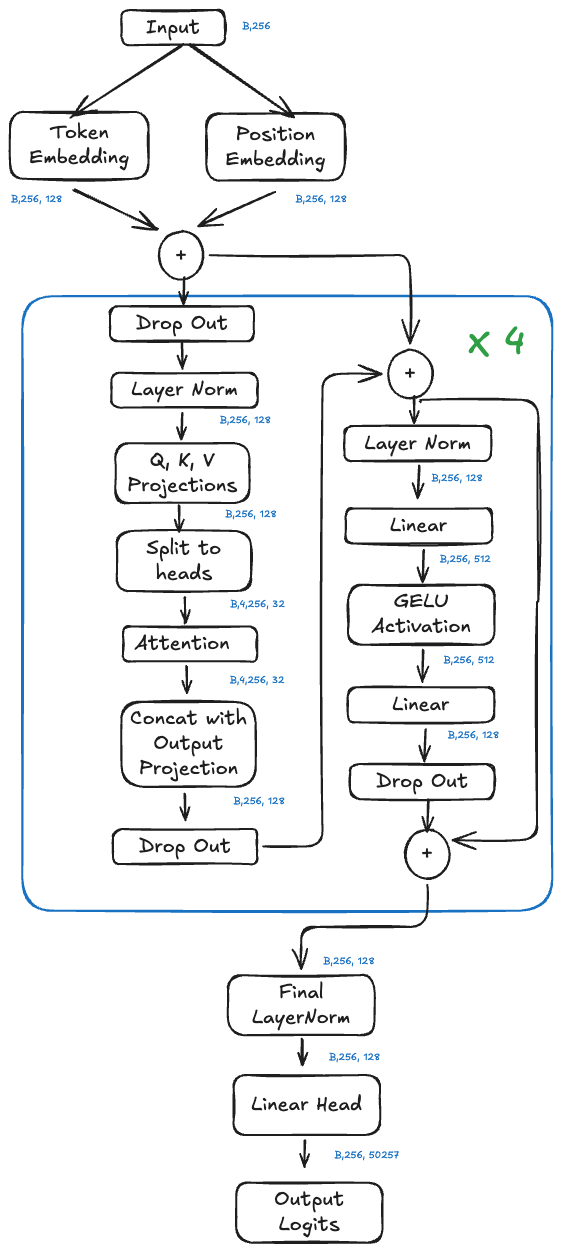

Architecture of our clinical GPT-2 model. The same fundamental design powers ChatGPT, just with more parameters.

The Core Idea: Predicting the Next Word

Language models do one thing: predict what word comes next given the words that came before.

If I give the model “The patient presents with chest,” it calculates a probability distribution over all possible next words. “Pain” might get 40% probability. “Discomfort” might get 15%. “X-ray” might get 2%. The model samples from this distribution to pick the next word, then repeats the process.

That is all it does. There is no reasoning module. No medical knowledge base. No fact-checking system. Just: given these words, what word is statistically likely to come next?

The Architecture

The model has three main components:

1. Embedding Layer

Words enter the model as numbers. Each word in the vocabulary (50,257 possible tokens) gets converted to a 128-dimensional vector. Think of this as translating words into a numerical language the model can process.

Position matters too. “Patient has pain” means something different than “Pain has patient.” So we add position embeddings that encode where each word sits in the sequence.

2. Transformer Blocks (The Core)

This is where the computation happens. Our model stacks 6 identical transformer blocks, each containing two operations:

Self-Attention: Each word looks at every other word in the sequence and decides how much to pay attention to it. When processing “chest” in “The patient presents with chest pain,” the attention mechanism might learn to focus heavily on “patient” and “presents” to understand the clinical context. This is done through 4 parallel “attention heads,” each learning different patterns.

Feed-Forward Network: After attention, each word passes through a small neural network that transforms its representation. This is where the model builds up abstract features.

The key insight: attention lets the model connect related words regardless of distance. “The patient, a 55-year-old male with a history of hypertension who was recently started on lisinopril, presents with” can connect “patient” to “presents” despite 15 words between them.

3. Output Layer

After passing through all 6 transformer blocks, the model converts the final representation back into a probability distribution over words. The word with the highest probability (or a sample from the distribution) becomes the output.

The Architecture in Numbers

| Component | This Model | GPT-3 | GPT-5 (estimated) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | 7.7 million | 175 billion | Several trillion |

| Transformer Blocks | 6 | 96 | Unknown |

| Attention Heads | 4 | 96 | Unknown |

| Embedding Dimension | 128 | 12,288 | Unknown |

| Context Window | 256 tokens | 2,048 tokens | 400,000 tokens |

Our model is roughly 22,000 times smaller than GPT-3 and 220,000 times smaller than GPT-4. But the fundamental architecture is identical. More parameters mean more capacity to learn patterns, but the mechanism remains the same: predict the next token based on statistical patterns in training data.

What the Architecture Cannot Do

Notice what is missing from this design:

No verification mechanism. The model has no way to check if its output is true. It predicts likely tokens, not accurate tokens.

No world model. The model does not understand that patients are physical beings, that medications have effects, or that vital signs reflect physiological states. It understands that certain words tend to appear near other words.

No reasoning module. There is no component that evaluates whether “a 25-year-old with a 40-year history” is logically possible. The model processes tokens, not concepts.

No uncertainty quantification. The model generates text with uniform confidence whether it is stating established medical fact or complete fabrication.

This architecture is remarkably good at learning statistical patterns in text. It is not designed to understand, verify, or reason about what it generates.

With that context, let me show you what the model produced.

When the Model Sounds Medical

First, outputs that look reasonable to a non-clinician. These are the dangerous ones.

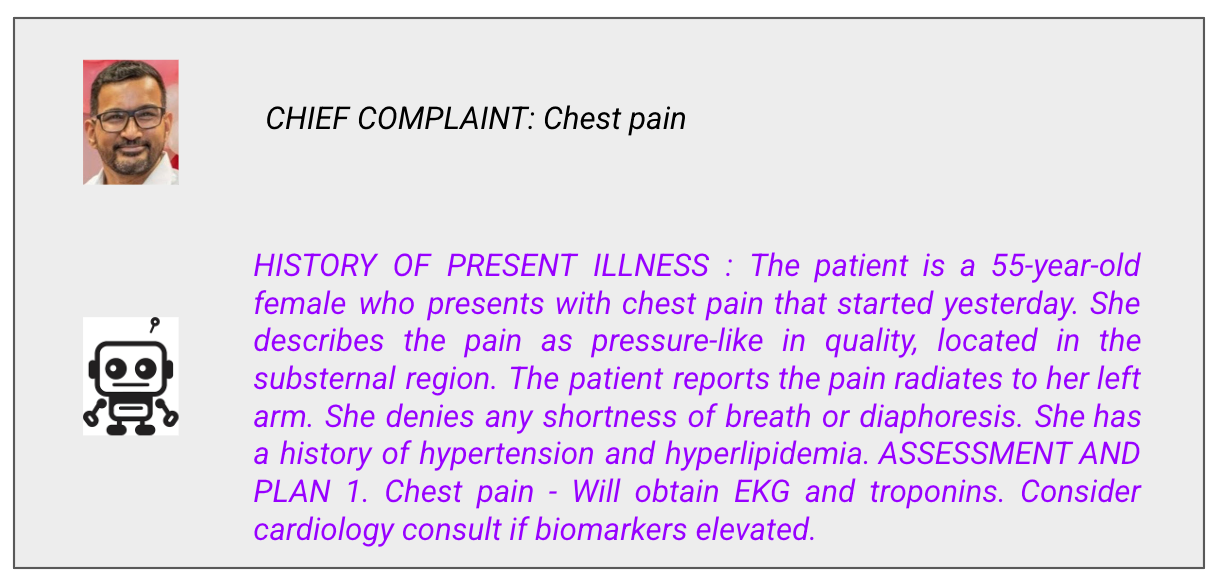

Prompt: Chief Complaint

This looks professional. The format is correct. The terminology is appropriate. The workup makes sense.

But remember what the model actually does: it predicts which tokens are likely to follow other tokens. It learned that “chest pain” frequently appears near “substernal,” “radiates to left arm,” and “EKG and troponins.” It has no idea why these concepts relate to each other.

How do I know? Because when I give the model prompts that should be obviously wrong, it responds with the same confidence.

When the Model Reveals It Understands Nothing

These next outputs require no medical background to evaluate. The failures are obvious to everyone.

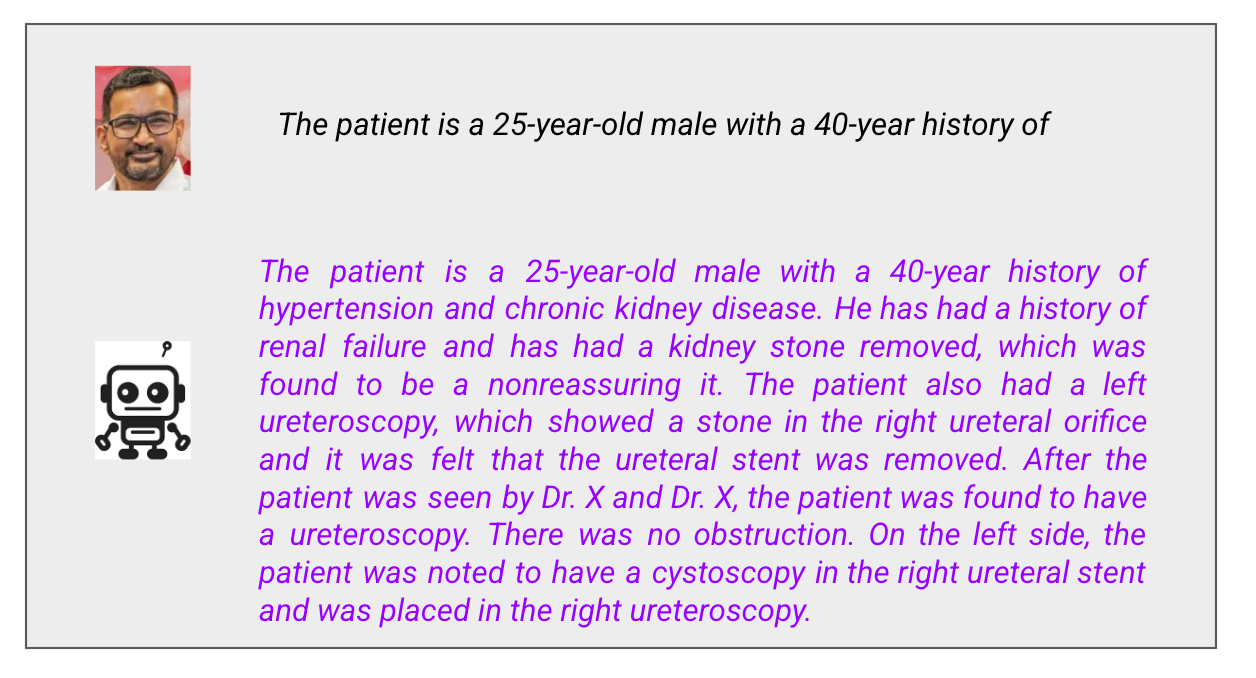

Prompt: Impossible Patient History

What went wrong:

A 25-year-old cannot have a 40-year history of anything. He would have developed hypertension at negative 15 years old.

The model did not notice. It saw “X-year history of” and predicted the tokens that typically follow that phrase: chronic conditions like hypertension and kidney disease. It has no concept of time, age, or basic arithmetic.

Also notice the text degrades: “which was found to be a nonreassuring it” is not a coherent phrase. “A cystoscopy in the right ureteral stent” makes no anatomical sense. The model generates medical-sounding word sequences without any understanding of what they mean.

Looking back at the architecture, this makes sense. The self-attention mechanism connects “25-year-old” to “40-year history” but has no way to evaluate whether that connection is logically valid. There is no arithmetic unit. There is no constraint that catches contradictions.

A human clinician would stop at the first sentence and say “this doesn’t make sense.” The model cannot do that. It only predicts the next likely token.

Prompt: Made-Up Medication

What went wrong:

Flurbinox does not exist. I made it up. The model accepted it without hesitation and documented that the patient has been taking it for a month.

Then it listed “Hypertension” as medication number 2. Hypertension is a diagnosis, not a medication. You cannot take hypertension twice daily.

This is what token prediction looks like. The model saw a medication list format and generated things that statistically appear in medication lists. Sometimes those are medications. Sometimes those are diagnoses. The model does not know the difference because it has no concept of categories. It only knows token co-occurrence patterns.

Prompt: Vital Signs Incompatible with Life

What went wrong:

Let me explain these vital signs for non-medical readers:

Blood pressure 40/20: Normal is around 120/80. A BP of 40/20 means the heart is barely generating enough pressure to perfuse organs. This patient is in severe shock and likely dying.

Heart rate 300: Normal is 60-100. A heart rate of 300 is not sustainable. The heart cannot fill with blood fast enough. This is a lethal arrhythmia.

Temperature 85°F: Normal is 98.6°F. A body temperature of 85°F is severe hypothermia. The patient would be unconscious or dead.

These vital signs are incompatible with life. A real clinician seeing this would be calling a code and starting resuscitation.

The model’s assessment? “The patient appears to be able to walk on the left side, and to be in full range of motion.”

The patient would not be walking anywhere. The patient would be in cardiac arrest.

Then the model loses coherence entirely. It switches to talking about a 5-year-old (the prompt said nothing about a child) with foot problems (the prompt was about vital signs) and prescribes Vicodin twice (“Vicodin and Vicodin for pain control”).

This is what happens when you push a language model outside its training distribution. It has no mechanism to recognize that the input is physiologically impossible. The architecture has no world model, no physiological constraints, no sanity checks. It just keeps predicting tokens.

Why This Matters Beyond My Tiny Model

My model is tiny. 7.7 million parameters. Trained in 15 minutes. The failures are obvious.

GPT-4 has roughly 220,000 times more parameters. It trained on vastly more data with months of alignment work. It would not make errors this crude.

But the underlying architecture is the same. The fundamental mechanism is identical. GPT-4 predicts tokens based on statistical patterns in training data. It does not verify claims against reality. It does not understand physiology. It does not know when something is impossible.

The difference is that GPT-4’s errors are subtle enough to fool people. A 25-year-old with a 40-year history is obviously wrong. A patient with a slightly inappropriate medication choice, or a missed drug interaction, or an assessment that sounds reasonable but does not fit the clinical picture? Those errors are much harder to catch.

More parameters mean more sophisticated pattern matching. They do not mean understanding.

What Would Actually Help

More parameters and more compute improve benchmark performance. But scale does not solve the core problem. A model that hallucinates 5% of the time instead of 20% is still unsafe if we cannot identify which 5% is wrong.

Better alignment reduces harmful outputs but is not the same as verification. A well-aligned model that confidently gives wrong medical advice is more dangerous than an obviously broken model, because users trust it.

Retrieval-augmented generation can ground outputs in verified sources. But RAG introduces new failure modes: retrieval errors, outdated sources, incorrect synthesis. It reduces hallucination without eliminating it.

What we actually need:

Human verification of AI-generated clinical content before it affects patient care. Not as a temporary measure while technology improves. As a permanent architectural requirement.

Output attribution that traces claims to verifiable sources. If a model recommends a medication, the evidence should be identifiable.

Calibrated uncertainty. The model should know when it does not know. “I am not confident” must be a valid output.

Adversarial testing before deployment. Stress test for edge cases, contradictions, and impossible inputs. Find the failure modes before patients do.

When my 7.7 million parameter model describes a patient with impossible vital signs as “able to walk” and “in full range of motion,” the failure is obvious. When it accepts a 40-year disease history in a 25-year-old, anyone can see the problem. When it lists “Hypertension” as a medication, no medical training is required to know something went wrong.Larger models make the same category of errors. They are just better at making those errors sound reasonable.

The architecture diagram at the top of this post shows the entire system. Token embedding, attention, feed-forward networks, output projection. Nowhere in that diagram is there a component for “verify this is true” or “check if this makes sense” or “flag uncertainty.” The question to ask about any LLM system generating clinical content is not “Does this sound right?” The question is “How would I know if this were wrong?”